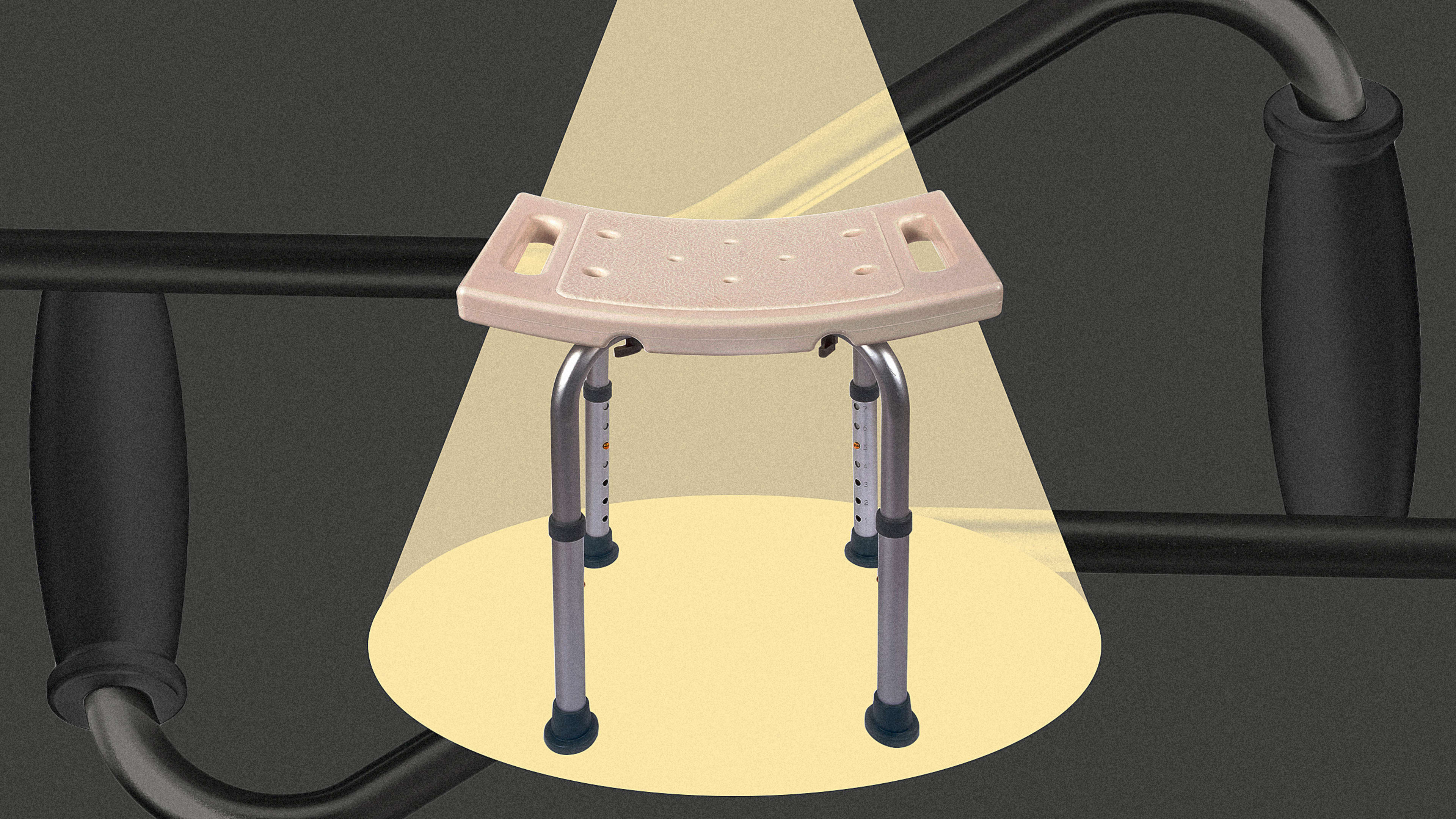

For most of us, thinking about the experience of aging conjures up imagery of golf, relaxing, and RV trips—illustrations that are idyllic, but severely outdated. Our minds also drift to all-too-stereotypical products like Life Alert and cold, clinical bath supports. Suffice to say, the landscape of products for older adults is a depressing sea of beige and stainless steel.

Ten thousand people are turning 65 every day in the United States, and all boomers will be 65 by 2030, but the realities of life after 65 often look far richer and more diverse than our cultural stereotypes would suggest. Older adults are living longer, and they have big and dynamic goals and aspirations. They are starting new businesses, adopting new tech, and more likely to try new things. Older adults are also the wealthiest age group, accounting for 53% of all household wealth, according to data from the Federal Reserve. Additionally, those 50 and up are responsible for about 50% of all consumer spending.

The opportunity to apply great design to products and services for older adults is massive, but doing it successfully will require looking beyond our entrenched narratives about this demographic and involving them in the design process. Most importantly, it should force us to think about how we can design for richer, more connected, and more purposeful lives—not just longer ones. So, how do we shed our traditional views of design for the colossal aging market and elevate our expectations?

It starts with framing

Words matter, and the opportunity to reimagine what aging looks like can’t be met with the language we currently use to describe this incredibly nuanced and variable life stage. The first step toward more age-inclusive design is simply opening our design thinking to encompass what’s possible later in life—instead of focusing only on what isn’t.

The FrameWorks Institute has made good headway here, building out a library of research and tools on the impact of the words we use and how they can often get in the way of innovation, policy, and progress. According to its brief on Framing Strategies to Advance Aging and Address Ageism: “Reframing the issue [of aging] requires disrupting the ‘othering’ of older people and sending the message that older age, like any other time in life, involves both challenges and opportunities. Why? Our research shows that negative assumptions about aging held by the public lead them to disassociate themselves from aging and take the fatalistic stance that nothing can be done to improve aging outcomes.”

For an example of this “othering” in action, look no further than most home accessibility aids designed for older adults. They solve a distinct need for people with mobility challenges, but their design is distinctly “othering.” Many of these products have a clinical, almost hospital-like quality that screams old, frail, and uncool. Similarly, there is a distinct absence of brands and ideas that recognize the potential and richness of life after 65—or that there even is life after 65.

Chip Conley and others like him are paying more than lip service to this issue by focusing on what’s possible instead of what’s not. Conley recognized that the framework of a 40-year career followed by a sedentary retirement is outdated, which led him to found the Modern Elder Academy (MEA). MEA gives older adults the space and tools to reenvision their lives and think about midlife as a renaissance instead of a peak followed by decline. The Academy helps students reinvent themselves through re-skilling, upskilling, volunteering, mentoring, storytelling, and even finding a second or third career. This kind of support can be invaluable as people reimagine their purpose and how they contribute to their communities.

As professor of design Jeremy Myerson states in his TED Talk, “we need to decide if we want a life full of years or years full of life.” He argues that we must move beyond a medical model where aging is seen as a disease that must be cured to a social model where design is applied to keep older adults integrated into society. While this may seem like a simple shift, it will take a lot of energy and focus—our negative cultural narratives and stereotypes about aging are deeply rooted.

Designing for and with older adults

To redesign the experience of aging, brands and designers must involve older adults in the process. We are starting to see companies like Eargo applying a human-centered design approach to traditionally aging-focused categories (in Eargo’s case, hearing aids) to create products that are desirable, not just functional. “It’s an augmentation of abilities, not fixing a disability,” according to design firm partner Matt Rolandson. Fastidiously listening to true market needs and designing accordingly, Eargo went public in October 2020 with an initial public offering worth $141 million.

In the design world, Ideo broke the mold by getting to know the market and designing for aging, a need that wasn’t previously considered “designable.” In 2015, the firm hired 89-year-old conceptual designer Barbara Berskind for an exploratory project and, over the years, they’ve relied heavily on her for aging-related projects that honor and respect older adults. For Berskind and Ideo, age is an advantage, and both agree good designs are meant for everybody. More recently, Ideo has developed a toolkit around Design on Aging that serves as a handbook to explain how design can enhance the lives of older adults.

To take advantage of this burgeoning market opportunity, designers and marketers will need to start recognizing the nuances of the audience. The agency and research firm Age of Majority recently released research identifying 11 unique personas within the older adult audience—an intricate segmentation that underscores the fact that we have been so focused on age alone and ignored the other complexities that make people human and drive the need for good design.

It’s encouraging to see some brands waking up to this opportunity and beginning to reenvision what the aging experience looks like, but we need to expand our “design brief” to consider how we enable older adults (including ourselves, if we are lucky enough to get to that point) to live richer and more purposeful lives. We must push past the impulse to hide or solve aging, and instead embrace and celebrate it. Changing the conversation and our expectations will create room and support for all of us to reinvent ourselves—at any stage of life.

Riley Gibson is the president of Silvernest, an online home-sharing service designed to pair boomers, retirees, empty nesters, and other aging adults with compatible housemates.

Recognize your brand’s excellence by applying to this year’s Brands That Matter Awards before the early-rate deadline, May 3.